APIs or application programming interfaces of popular services are used by numerous startups to bring valuable services to the general public. API websites such as ProgrammableWeb is one of the more popular sites offering a variety of plugins and mashup examples.

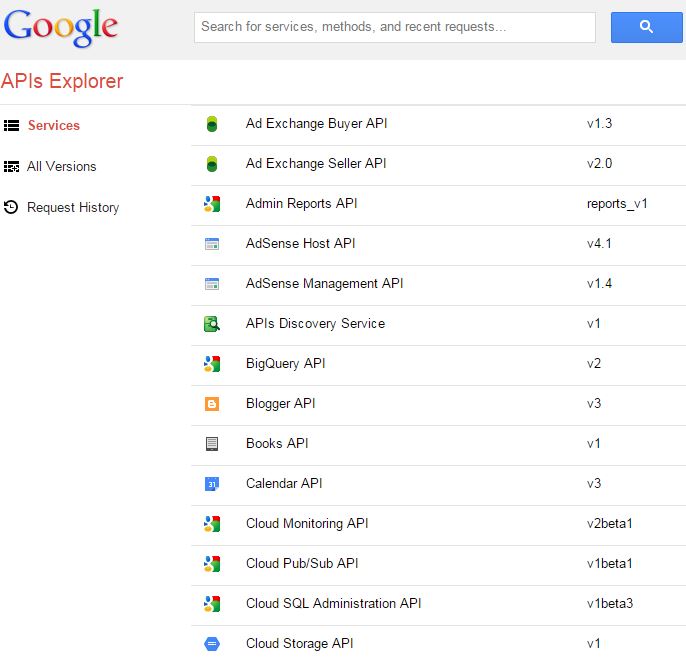

Companies such as Facebook, Foursquare and the Google’s API explorer share data with programmers, data that becomes all but the fabric of apps which can do some pretty amazing things. By combining various datasets with user input, a new killer app can provide better personalization and enhanced user experience.

There is, of course, a discrepancy between what user data is provided by an API and what the data holder actually has in store. For example, Facebook seems quite democratic in terms of providing user data – users can control what data gets shared, after all – whereas other hoarders (especially e-stores) are rather possessive of their data. Facebook’s API is, however, inevitably of a limited scale as unlike for Twitter, most of their data (like the vast majority of status updates) isn’t public. Publicly available data serves for grandiose, location-spanning projects like CityBeat, which attempts to map ‘the heartbeat’ of the city via social media updates and maps.

As for combining data, there’s a lot to tell for projects like DontEat.at that warns FourSquare users if a NYC restaurant they’ve checked in at has been flagged for possible health code violations. Here the app merges data from two ‘locations’, that is, FourSquare and a list maintained by the authorities, giving people better odds against food poisoning. Such projects showcase creative use of data and are of real use to the public.

The best results are, of course, gained when data is abundant. Such is the case for NeighborhoodScout, which aggregates Census data and other sources, visualizing with the help of Google Maps, in order to bring neighborhood data like crime rates, property prices, and much more to those wishing to relocate.

Other apps are more fun-oriented. Quizzes, personality readers and the likes don’t really influence people’s decisions, or, well, anything (except perhaps their friends’ opinion of them), but they do make good filler for the time that should be spent working.

Conclusion

There is inherent tension between the three parties involved. The big hosts want to benefit from their data, not just share it. Developers naturally want to mine the vast data archives to come up with ever crazier killer apps. Users, however, are only likely to want to share their data only if they see a tangible payoff, otherwise they’re mostly privacy advocates. There isn’t a simple solution, but it can very well be argued that the data hosts should be willing to provide user-consented access to data they are already using themselves.

By Lauris Veips